What does it take to build the perfect team?

Like many companies, Google executives believed that the best teams were made up of the best people. In the words of Julia Rozovsky, an analyst in Google’s People Operations division, “Take one Rhodes Scholar, two extroverts, one engineer who rocks at AngularJS, and a PhD. Voila. Dream team assembled, right?”

“We were dead wrong,” says Rozovsky, who set out to on Project Aristotle, Google’s two-year project aimed at uncovering what characteristics make up the perfect team. Essentially, why some teams excel while others fall behind. Researchers interviewed over 200 employees and looked at more than 250 attributes of over 180 active Google teams. Their findings have proved particularly useful inside their own organization, which other enterprise teams should take note of.

What they discovered surprised them: Who is on a team matters less than how the team members interact, structure their work, and view their contributions.

But the most surprising discovery? The key to team success is psychological safety.

Psychological Safety and the Perfect Team

After the success of Google’s Project Oxygen research, where the company’s People Analytics team studied what makes a great manager, Google researchers applied a similar method to identify the characteristics that make up the perfect team.

The assumption was that the best teams were comprised of talented individuals. But after recruiting statisticians, organizational psychologists, sociologists, engineers and researchers to help solve the riddle, no matter how researchers arranged the data, it was almost impossible to find patterns.

As Abeer Dubey, a manager in Google’s People Analytics division, tells the New York Times, “We looked at 180 teams from all over the company. We had lots of data, but there was nothing showing that a mix of specific personality types or skills or backgrounds made any difference. The ‘who’ part of the equation didn’t seem to matter.”

In fact, some groups that were ranked among Google’s most effective teams were comprised of friends who socialized outside of work. Others were made up of people who were strangers away from the office. Some groups had strong managers and others preferred a less hierarchical structure.

But what was most astonishing to the researchers were two teams with nearly identical makeups but radically different levels of effectiveness.

The researchers were stumped.

“At Google, we’re good at finding patterns,” Dubey says. “There weren’t strong patterns here.”

It wasn’t until the researchers started considering some intangibles that things started to fall into place.

Rozovsky tells the New York Times they kept coming across research by psychologists and sociologists that focused on what was known as “group norms.” Essentially, traditions, behavioral standards and unwritten rules that govern how people behave when they’re together.

Norms are an unspoken and often unwritten set of informal rules that govern individual behaviors in a group. Group norms, according to the Business Dictionary, vary based on the group and issues important to the group. Without group norms, individuals would have no understanding of how to act in social situations.

The Project Aristotle researchers found that the right team norms could raise a group’s collective intelligence, whereas the wrong norms could harm a team, even if each individual was exceptionally bright.

Establishing the Right Team Norms

Charles Duhigg, a journalist and author of “Smarter Faster Better” who spent time working with the Project Aristotle team, says it doesn’t matter who is on a team so much as how those people interact.

“You could have enemies on a team together or you could have strangers or friends or people who don’t get along at all; you could have all introverts or all extroverts, and as long as they treat each other a certain way, as long as there’s a certain culture, then that team will gel,” Duhigg says.

In order for a team to achieve psychological safety, there are two characteristics that matter most:

- Equality in conversational-turn taking, or when everyone speaks roughly the same amount during a meeting; and

- Ostentatious listening, or when members of a team demonstrate they are actively listening by repeating what has just been said and making eye contact.

“If you have these two characteristics, conversational turn-taking and ostentatious listening, it creates what psychologists refer to as psychological safety,” Duhigg said. “[It’s] the single greatest correlate with a group’s success.”

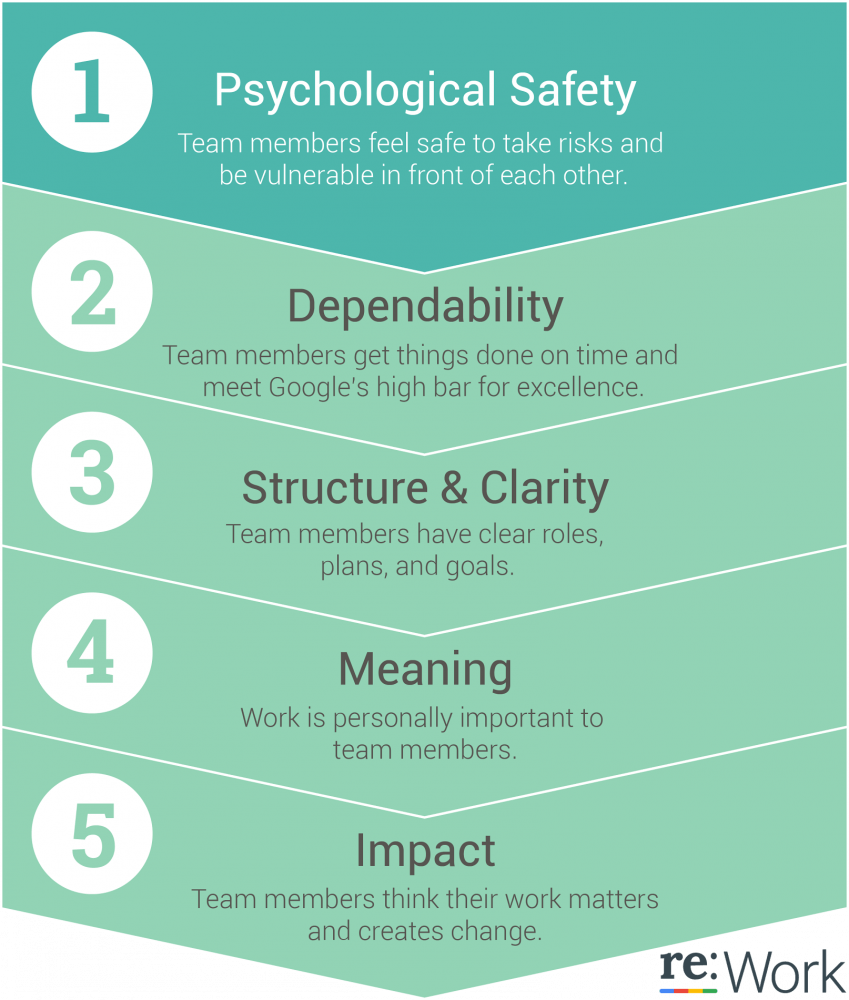

Further, the researchers found there are five key dynamics that set successful teams apart from other teams:

- Psychological safety: Can we take risks on this team without feeling insecure or embarrassed?

- Dependability: Can we count on each other to do high quality work on time?

- Structure and clarity: Are goals, roles, and execution plans on our team clear?

- Meaning of work: Are we working on something that is personally important for each of us?

- Impact of work: Do we fundamentally believe that the work we’re doing matters?

According to Rozovsky, psychological safety is “far and away the most important” of the five dynamics and it underpins the other four.

“Taking a risk around your team members seems simple. But remember the last time you were working on a project. Did you feel like you could ask what the goal was without the risk of sounding like you’re the only one out of the loop? Or did you opt for continuing without clarifying anything, in order to avoid being perceived as someone who is unaware?” Rozovsky says.

“Turns out, we’re all reluctant to engage in behaviors that could negatively influence how others perceive our competence, awareness, and positivity. Although this kind of self-protection is a natural strategy in the workplace, it is detrimental to effective teamwork.”

The research found that people who feel psychologically safe on teams are more likely to admit mistakes and to take on new roles. They’re also less likely to leave for another job, more likely make the most of diverse ideas from their teammates, bring in more revenue and, ultimately, are more successful.

Interestingly, evolutionary adaptations can explain why psychological safety is both fragile and vital to success in uncertain, interdependent environments, according to The Harvard Business Review. The brain processes a provocation by a boss or competitive colleague as a life-or-death threat. The amygdala, which plays a key role in the brain when it comes to processing emotions, sets off the fight-or-flight response, hijacking higher brain centers. The brain then shuts down perspective and analytical reasoning.

So while the fight-or-flight reaction might save you in life-or-death situations, it handicaps the strategic thinking people need in modern-day companies when working on teams.

Practicing Psychological Safety at Work

We’re spending more time working in teams than ever before. So says a study published in The Harvard Business Review that notes the time spent managers and employees spend on team activities has blown out by 50 percent or more over the past two decades. On top of that, at many companies more than three-quarters of an employee’s day is spent communicating with colleagues.

So being aware of your and your employees’ fight-of-flight response during team activities and meetings is crucial to the success of your projects. But how can you increase psychological safety for teams in your organization?

Organizational behavioral scientist Amy Edmondson of Harvard first introduced the construct of “team psychological safety.” She defines it as “a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking.”

In her TEDx talk, Edmondson offers three simple things people can do to foster team psychological safety:

- Frame the work as a learning problem, not an execution problem

- Acknowledge your own fallibility

- Model curiosity and ask lots of questions

Building on Edmondson’s considerations, Paul Santagata, Head of Industry at Google, shares six key areas companies should focus on in order to foster psychological safety in High-Performing Teams Need Psychological Safety. Here’s How to Create It:

1. Approach conflict as a collaborator, not an adversary

People hate losing more than they love winning. Santagata says a perceived loss triggered people to attempt to reestablish fairness through competition, criticism or disengagement — a form of workplace-learned helplessness. When conflicts come up in a team environment, the win-win outcome for companies is to avoid triggering a fight-or-flight reaction by encouraging employees to ask themselves, “How could we achieve a mutually desirable outcome?”

2. Speak human to human

Many teams experience a “who did what” confrontation. Fundamental to this type of conflict is recognizing universal needs such as respecting competence, social status and autonomy. Santagata says recognizing these deeper needs naturally elicited trust and promoted positive language and behaviors. Santagata has led his own team through a “Just Like Me” reflection that asked them to consider:

- This person has beliefs, perspectives, and opinions, just like me.

- This person has hopes, anxieties, and vulnerabilities, just like me.

- This person has friends, family, and perhaps children who love them, just like me.

- This person wants to feel respected, appreciated, and competent, just like me.

- This person wishes for peace, joy, and happiness, just like me.

Reflecting on these points reminds people that even during arguments, the other person is just like them and wants to walk away happy.

3. Anticipate reactions and plan countermoves

Anticipating how someone might react to a conversation could help ensure what you say will be heard, versus the other person hearing an attack on their identity or ego.

Santagata suggests confronting difficult conversations head-on by preparing for likely reactions. For example, gathering concrete evidence to counter any defensiveness when discussing sensitive issues. Santagata asks himself, “If I position my point in this manner, what are the possible objections, and how would I respond to those counterarguments?”

Looking at a discussion from a third-party perspective might help expose any weaknesses in your position and encourage you to rethink your argument. Specifically, Santagata asks:

- What are my main points?

- What are three ways my listeners are likely to respond?

- How will I respond to each of those scenarios?

4. Replace blame with curiosity

University of Washington research shows that blame and criticism reliably escalate conflict, leading to defensiveness and eventually to disengagement. Santagata says the alternative to blame is curiosity. If you believe you already know what the other person is thinking, then you’re not ready to have a genuine conversation. Santagata suggests adopting a “learning mindset” and going into conversations knowing that you don’t have all the facts.

- Try stating problematic behavior or outcomes as an observation and use factual, neutral language, e.g. “In the past two months there’s been a noticeable drop in your participation during meetings and progress appears to be slowing on your project.”

- Engage the other person in an “exploration,” e.g. “I imagine there are multiple factors at play. Perhaps we could uncover what they are together?”

- Ask for solutions. The people who are responsible for creating a problem often hold the keys to solving it. Ask directly, “What do you think needs to happen here?” Or, “What would be your ideal scenario?” Another question leading to a solution is: “How can I support you?”

5. Ask for feedback on delivery

Asking for feedback at the conclusion of a conversation can disarm the person you’re speaking to and help to uncover any blind spots in communication while at the same time promoting trust. Santagata closes difficult conversations with these questions:

- What worked and what didn’t work in my delivery?

- How did it feel to hear this message?

- How could I have presented it more effectively?

6. Measure psychological safety

Santagata regularly asks his team how safe they feel and what could increase their feeling of safety. His team also routinely completes surveys on psychological safety and other team dynamics.

Fostering Psychological Safety in the Modern Workplace

Psychological safety in the workplace is all about creating an environment where employees feel accepted and respected and aren’t afraid to screw up.

The concept is nothing new. Scholars first raised the notion of psychological safety in the 1960s and it has continued to grow in popularity. But with the addition of Google’s research, the evidence is now clear: psychological safety matters a great deal to the bottom line.

The research shows that people who feel psychologically safe tend to share more ideas, are more innovative, learn from their mistakes, and are motivated to improve their team or company.

Companies that want to create psychological safety should have inclusive leaders who can demonstrate tolerance of failure by acknowledging their own fallibility.

At the same time, it’s important to distinguish between psychological safety and accountability. While psychological safety promotes that people shouldn’t be punished for simple errors, it doesn’t mean there aren’t consequences for a lack of performance.

Ultimately, you can rest assured that Google has lost no time in applying what it has learned from the Project Aristotle research, which took its name from Aristotle’s famous quote, “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts” — Google researchers believe employees could do more working together than alone.

When considering how to run your own team, or company, taking cues from market leaders like Google can help to set a company culture that others have proven to work. It’s also important to keep gaining inspiration from anywhere you can. On that note, here are 40 must-read blogs for leadership.